Endorsements for Sing to Me and I Will Hear You – The Poems

These passionate, heartrending poems of love and grief came rushing into the author’s life nine months after the death of her husband. Elaine and Francis McGillicuddy shared a “Big Love,” which death has only deepened.As she writes, “we’re still moving together / though the melody’s new.” Anyone who has mourned the death of a beloved partner will find solace, wisdom and, yes, even joy here.

Gloria Hutchinson

— author of Glimmers of God Everywhere:

Catching Sight of the Daily Divine

What lies at the heart of these poems is the daily work of love – to keep a clear space open for the presence of the Beloved. These are songs, true, but also prayers.

Alfred DePew

— author of The Melancholy of Departure and Wild & Woolly:

A Journal Keeper’s Handbook

Readers will be moved by the contemplative simplicity and spiritual insight of these poems. A wonderful testament of enduring love, a comforting companion to those who grieve.

Greg Mogenson

–Jungian analyst and author

These poems strike a blessed chord of grace-filled compassion.

Marvin M. Ellison

— theologian and author of Making Love Just:

Sexual Ethics for Perplexing Times

A loss of long ago or a more recent one finds a home in these lovely images. One realizes that one’s private experience of loss is shared and understood by another. We become a community of sojourners whose emptiness is filled with simple ways to notice, look more carefully, and remember. A long, loving relationship and the last months of a life documented here with tender beauty reveal just how sacred life is, how sacred its passing, and its remembering.

Joseph Kilikevice, OP

— Founder and Director of Shem Center for Interfaith Spirituality

In Review

Poems Forged in Grief Echo a Formidable Love

by Gloria Hutchinson

(Published in the May/June 2012 issue of CORPUS Reports www.corpus.org)

“A poem begins with a lump in the throat,” wrote Robert Frost. And anyone who reads Elaine G. McGillicuddy’s first volume of poems, Sing to Me and I Will Hear You – The Poems is bound to share the truth of Frost’s observation. McGillicuddy, of Portland, ME, lost her husband Francis to cancer on Jan. 3, 2010. He was 82 and they had been married for forty years.

Their love story is particularly poignant because, when they first met, she was an Ursuline nun and he was a diocesan priest. They shared a commitment to the peace movement during the Vietnam war. Their mutual devotion led them to marry and pursue together interests in yoga, Pax Christi, war tax resistance, permaculture, the Dances of Universal Peace, and membership in CORPUS.

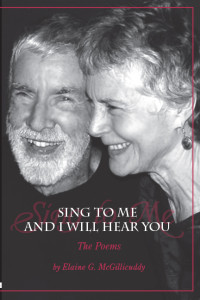

The reader meets the McGillicuddys on the cover of Sing to Me. All the poems can be considered a commentary on what is revealed by that portrait. The faces of husband and wife reflect the unrestrained joy of mated souls saturated with love for each other, for life, and for its Source.

Poet Jane Hirschfield points out that poetry “is based on a thoroughly lived life.” Elaine McGillicuddy did not become a poet until her 75th year. But her writing draws on the deepest of wells, a life and a love thoroughly lived. She wrote these 65 poems because she needed “a reason to go on living.” They are the fruit of her daily contemplative prayer or “sitting practice” which she does wrapped in her husband’s shroud as a prayer shawl. Reading them will be a healing experience for bereaved widows and widowers, friends and kin.

One of McGillicuddy’s most affecting poems reveals the origins of her memorable title. “Duet” begins with Francis’ words to his wife when he knew that he would not survive the excruciatingly painful bone cancer: “As death approaches me, . . . / even if I seem beyond your reach, / sing to me and I will hear you.” She did. And she knew that he did.

In the poem’s second movement, McGillicuddy celebrates her husband’s transformed presence which she experiences as right here, right now. She knows that Francis lives on. “When Great Mystery beckoned, you entered Her depths, / but left the door ajar for me. / Now I can hear you sing!”

McGillicuddy’s narrative poems draw us into the small case events of a widow’s daily life where familiar settings have the power to wound or hearten. “Big Love” recounts a seemingly minor incident wherein the poet is driving home from a visit to her chiropractor a few months after Francis’ death. She suddenly remembers how he would say, “Drive carefully.” / (revealing love’s concern).”

The remembrance of her husband’s voice, emblematic of his manly protectiveness, makes McGillicuddy’s heart swell with the recognition of “so much love / I was surprised, / said out loud, still driving – / “It’s big! IT”S BIG – YOUR LOVE!” Her profound perception assures the reader that love not only does not die after a loved one’s death, neither is it diminished. It expands.

The lyrical and alliterative “The Tang” compares the McGillicuddys’ wedded life to a “dance all these years, / its rhythm and beat pulses now in my life / with such force/ I can feel both your hand and your step.” The poem closes with this telling stanza: “We’re still moving together / though the melody’s new.”

Several poems in this volume incorporate actual dialogue from the closing months of Francis McGillicuddy’s life, as his wife kept a journal to store up his precious words. One of the most memorable is “Whoever Heard” in which a hospice nurse at the home patient’s bedside asks him, “What’s holding you back?” / ”It’s the joy,” you said.”

A few of the poems are spiced with welcome humor. In “Hospital Walk,” McGillicuddy recalls how her husband demonstrated a squat to a surprised physical therapist and impishly proclaimed, “It’s yoga.” In “Two Firsts,” the poet connects Francis’ first radiation treatment with another first. She boasts to the therapist that “this man of mine, / 20 years ago / at 62 / kicked up / into his very first-ever / handstand.” (To those who knew him, this image of the lanky patient upended is delightful.)

Although most of the poems are focused entirely on husband and wife, “He Stood On Our Ladder” broadens the poet’s perspective and reminds us of both the McGillicuddys’ global concerns. The “he” of the title is an African youth who had fled persecution in Burundi. The poet has hired him to pick peaches, while she gathers the fallen fruit on the ground. He tells her his sad story yet breaks into song as he enjoys the beauty of the day.

The poet wonders if her husband, through his “loving communion” with her, continues to grow as she does in her new solitary life. She realizes that he is with the Source of life and can have nothing further to gain. But she concludes with these lines: “Yet remembering / this Wellspring, our God, counts / the very hairs on (our) heads,” / I know / that you grow when I do.”

Readers of this volume will likewise grow through their exposure to a rare relationship between two graced souls destined to share a formidable love. In their 40 years of marriage, the McGillicuddys gathered around them a widening community of peacemakers, earth-stewards, and justice-doers. They enriched the world as they found it.

I once visited a Unitarian-Universalist church in Portsmouth, NH, where the co-pastors were a married couple whose gifts visibly complemented one another. Remembering that holy and wholly human man and wife, I see in Elaine and Francis McGillicuddy what the Catholic Church deprived itself of by saying no to married priests.

Sing To Me And I Will Hear You is a beautiful book. Read it and be lifted up by the company of two priests, one on either side of the thin place separating this material world from the everlasting City of God. For, as Wallace Stevens observed, “The poet is the priest of the invisible.”

(Gloria Hutchinson, author, whose latest book is Glimmers of God Everywhere: Catching Sight of the Daily Divine, lives in Bangor, ME.)

Review

Posted on the Portland Maine Permaculture Meetup website in June 2012

by Merry Hall, author of Bringing Food Home: The Maine Example

Our Elaine McGillicuddy dedicates her book, Sing to Me and I Will Hear You – The Poems, to her recently departed and much beloved husband thus:

For Francis

who knew how to

“surrender to Mystery”

Elaine, too, surrenders to the Mystery that unfolds when a poet stands naked at the intersection of specific personal experience and universal Love. She opens her grief at losing Francis to death and her joy at finding him embraced by eternal Life.

By now your spinal cancer pain

has chained you to your bed.

I floss your teeth;

I help you pee.

And what do you say to me?

“O, what a wonderful moment this is!

My beloved’s here with me.

You look good, you feel good,

and you are so good to me.”

O Francis dear – What sweetness!

What love and brave acceptance!

You’re forever seared upon my soul.

What a gift! I am simultaneously humbled and inspired in the face of such love.

With her poem:

Pain’s sharp edge

cuts through appearance

of disappearance.

Heart’s remembering sharpens

sense to touch

new, you, now, any when.

Elaine reveals that I, too, can experience transcendence if I will only surrender to the immediacy of my emotions so deeply that I have only to dive in. The intimacy is astounding; the immediacy is breathtaking.

It is when we thus surrender that the poetry we co-create with the Universe washes through us unbidden, healing reader and writer alike:

These Poems

–custom-made maps

carefully drawn

By the Cartographer

Offering to show me

My way.

These poems

–like bells ringing out

my truth, resounding

through the clouds and darkness, guide

me home.

Letter from my former doctor, Daniel C. Bryant M.D.

Thank you so much for the Sing to Me book and CD. The poems tell such a moving story of love, loss, acceptance, trust, belief….And tell it with great poetic skill. “…but left the door ajar for me” is just the right way to talk of Great Mystery. “…hugging grocery bags for us” is just the right way to talk of those priceless daily moments we often overlook. “…sparing you/a widower’s pain” gives great perspective. And “…I pluck plump blueberries” is literally lip-smacking. Reminds me of my favorite doctor-poet William Carlos Williams – the plums that “were delicious/sweet/and so cold” in “This Is Just to Say.” And some of the other poems are Rumi-like in their subtlety.

I hope you keep writing, both for yourself and for others. Especially Francis.

Dan

A widow friend’s note:

“I thank you from the bottom of my heart. Your poems express what I feel but don’t have words for. Hearing it said, eases the ache.”

Note from Doug Rawlings, a founding member of Veterans for Peace:

“Your poems are beautiful, strong, deceptively simple. Profound in a real sense.”